“I wonder if the NBA will ever come back to Kansas City…”

During the first month in my move to Kansas City, I went to a bar nearby in Kansas City, Kansas called “Chicago’s“. It was a small bar that just served alcohol, no food (as typical with most bars in the Strawberry Hill area), and was mostly frequented by alums of Bishop Ward High School in Kansas City, Kansas, one of the oldest Catholic high schools in the State of Kansas. At the bar, I got into a conversation with somebody who was a heavy NBA and Oklahoma City Thunder fan (weird for me because I went to Gonzaga and most fans were Sonics fans and the Thunder brought up so many bad memories for them), and he said the quote above, and followed up with positive affirmation that it was going to happen soon in the near future.

“We built the Sprint Center, it’s a NBA-style arena. The downtown area, though not my thing, can attract people before and after games. It’s a sure thing man. They have to bring a NBA team back to Kansas City!”

Back then and to this day, I do agree with him in some regards. The Sprint Center is an arena that can adequately host a NBA franchise (or NHL franchise, should Kansas City ever want one) and is a considerable upgrade over the Kings’ former home, Kemper Arena. The Power and Light District is a good venue for NBA fans to get a bite before weekday games and a drink after them. And with the opening of the KC Streetcar, there is an avenue of public transportation that could ease game day parking anxiety for fans. If there ever was a time for Kansas City to acquire a NBA franchise, the next few years would be it.

However, I do not remain hopeful a NBA franchise will come back to Kansas City, even though I did buy this Charlie Hustle shirt a couple of days ago. For starters, the NBA is probably doing as well as it ever has in its organizational history. The game is slowly becoming the most global sport in the world, especially with FIFA and soccer having all kinds of organizational issues. NBA superstars are becoming household names, and their popularity and imprint on social media and the web has made the league more accessible to fans than other professional sports like the NFL and MLB which seem like “Insiders-only” clubs. (Though the NFL is a lot worse than MLB). And teams are playing good basketball, much better than the college variety that is being seen today. The Warriors clearly are one of the NBA’s best teams, but if you look around the league, there is growing parity, as multiple different teams have made the playoffs within the past five years. Competitively, the NBA is as good as it has ever been, and that has made it a hot ticket with not only passionate basketball fans, but casual fans who are looking for sporting excitement during the Winter and Spring months.

But, with all that being said, these factors hurt the prospect of a NBA franchise coming to Kansas City. With the game being better than ever, franchises are less likely to sell or move from their current locations. As of this moment, every NBA franchise seems to be on solid footing in their current location, and with revenue in the league getting higher and higher each year, NBA owners would be foolish to move during such a renaissance in the league’s history. And with that being said, expansion doesn’t look to be the best idea for the league either. There is a considerable diversity and depth of talent in the league, as each NBA team has a marketable Superstar they can build their franchise around. (With the exception of maybe the 76ers…but hey, maybe Dario Saric and Ben Simmons can reverse that trend!) Expansion would only dilute the talent pool in the league, and make the league less competitive, which wouldn’t help the national or global imprint the league currently has.

This was evident back in 1995, when the league expanded to 30 teams with the Toronto Raptors and the Vancouver Grizzlies. The league really didn’t have enough talent, and though the Raptors were able to climb toward respectability eventually, the Grizzlies struggled to find talent, and this inevitably led to their move to Memphis, as they could not generate enough fan interest to support their lackluster on-court product. If the league were to expand to two more teams, the same issue would rear its ugly hand, and it could be decades before the league adequately recovers competitively (the late 90’s and early 2000’s saw a lot of competitive imbalance due to expansion).

And lastly, there are other cities they right now would be more attractive sites for the NBA than Kansas City, as painful as that it is to write. Seattle is the front runner for relocation and expansion as they have the right figurehead (Chris Hansen) and fan base to attract a NBA franchise. Other cities like Anaheim (which almost got the Kings before the Maloofs decided at the last minute not to sell), and possibly Vancouver (with basketball now more popular than ever in Canada, the idea of a second franchise again in Vancouver makes sense; David Stern, in one of his last years as commissioner, also remarked that moving the franchise out of Vancouver was one of his biggest regrets). So, Kansas City isn’t exactly top on the queue of possible “relocation” or “expansion” spots, and that should deter any NBA fan in Kansas City of dreaming about the possibility of professional basketball being resurrected in Kansas City in the near or even distant future. Yes, Kansas City has the resources, but it may just be that the NBA and Kansas City will never be the right fit, which is unfortunate as Kansas City is becoming one of the more landmark and major cities in the Midwest, and it could expand the game’s popularity in the “Heart of America”.

That being said, even though the future for the NBA in Kansas City looks bleak, there is a rich NBA tradition in the city as one of the major franchises during the 70’s and 80’s. And one of the cooler things that happened in their history was their “joint-city” franchise from 1972-1975 when the Kings were known as the Kansas City-Omaha Kings. So, let’s take a brief look back at the history of this franchise when they were truly the “Heartland’s” NBA franchise.

The Kings franchise began in 1948-1949 as the Rochester Royals out of Rochester, New York. In just the franchise’s third year of existence, the Royals won the NBA Championship in 1951, which has been the only championship in franchise history. In 1956, the Royals moved to Cincinnati where they became the Cincinnati Royals. During their 15-year run, the franchise was mostly led by former Bearcat and future Hall of Famer Oscar Robertson, who averaged 29.3 ppg, 10.3 apg and 8.5 rpg in his 10 seasons with the Royals from 1960-1970 (he finished his last four seasons in Milwaukee). The franchise in Cincinnati experienced some success, as they made the playoffs six straight seasons from 196-1967 during the peak of Robertson’s career. However, they never made it past the conference finals, and after Robertson went to Milwaukee, the Royals suffered a couple of miserable seasons before they decided to move further west to Kansas City.

Because of the baseball team already being the Royals, the NBA team renamed their franchise the Kings in their move to heart of the Midwest. Originally, the Kings were supposed to play in three locations: Kansas City, Omaha and St. Louis. However, the plans for St. Louis fell apart shortly before the 1972-1973 season their first year in Kansas City and Omaha. The Kings split their games during their first two seasons between Municipal Auditorium in downtown Kansas City and the Omaha Civic Auditorium. While a classic arena, Municipal, even at the time, was hardly a NBA venue, as it only seated 7,316 people for games (nearly 2,000 less than the Omaha Civic Auditorium).

Now to people nowadays, the idea of a split-city franchise seems unheard of. With how big public funding is with arenas, and how much economic impact a NBA franchise has on a city, today, such a thing wouldn’t exist. Cities invest too much in their sport franchises to “share” with another city, and the splitting of revenue from merchandise and taxes would be an accounting nightmare. However, back in the day, when the NBA was still trying to compete with college basketball for fans and revenue, this was a lot more common, though in more minor instances. For example, the Boston Celtics used to regularly play games in Hartford, Connecticut (to reiterate the Celtics’ legacy as “New England’s Team”), and the Clippers used to split their home games between Los Angeles and Anaheim (the Clippers toyed with moving permanently to Orange County for a while as their Anaheim crowds consistently outdrew their Los Angeles ones). Even the Golden State Warriors are called “Golden State” for a reason, as they originally were going to split their home games between Oakland and San Diego after they moved from San Francisco (though they ditched this idea before even implementing it and simply made Oakland their exclusive home).

That being said, Kansas City-Omaha was really the only NBA franchise that had the two city identity, even if it only lasted for a few years. And to be honest, the idea really was a smart one. With Kansas City and Omaha being both border cities, the Kings were not just catering to two cities (like in the Clippers’ situation) or even two states (like the Celtics), but rather four states (Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska and Iowa). By being in Kansas City AND Omaha, the Kings really were trying to be the Midwest’s NBA team, and even though it was short-lived, the three years undoubtedly had some kind of impact in generating NBA fan interest in communities where the NBA, let alone basketball in general, is not necessarily enticing or a priority.

(And another underrated contribution: the Kings in Kansas City-Omaha introduced the name underneath the number, as seen below; even to this day, the Kansas City Omaha Kings jerseys stand the test of time in terms of their aesthetic value)

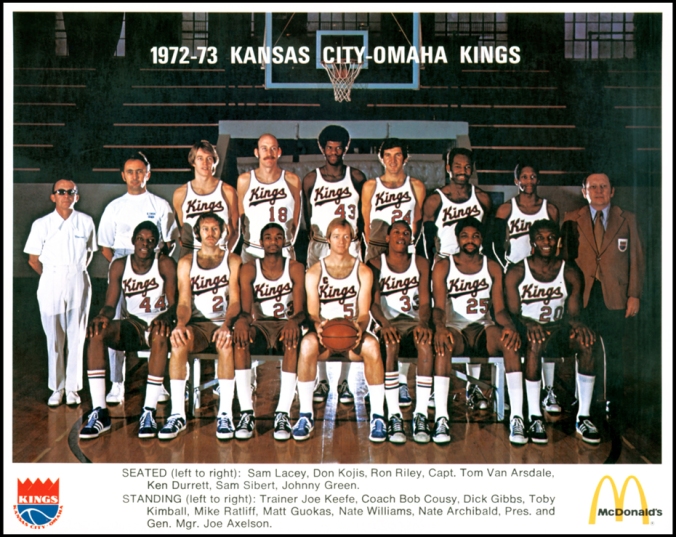

The Kansas City-Omaha Kings struggled in their first two years, finishing 36-46 under head coach and former Boston Celtics legend Bob Cousy, and then 33-49 in a year where the franchise saw three different head coaches. Cousy stepped down after a 6-14 start, they had 4 games led by interim coach Draff Young (which they lost all 4), and then the year was finished by Phil Johnson, who went a respectable 27-31 for the remainder of the year.

In Johnson’s first full season though, the Kings tasted their first morsel of success in the Midwest. In Kansas City, the Kings went from playing at the old Municipal to the newly opened Kemper Arena, state of the art at the time, and a much bigger venue than either Municipal or the Civic Auditorium in Omaha (Kemper sat 16,785 people). Because of access to this new arena in the West Bottoms, the Kings only played 11 games in Omaha during the 1974-1975 season, a significant downgrade from the previous two years, and a sign of things to come: the Kings decided to play solely in Kansas City and dropped the “Omaha” from their name the next season.

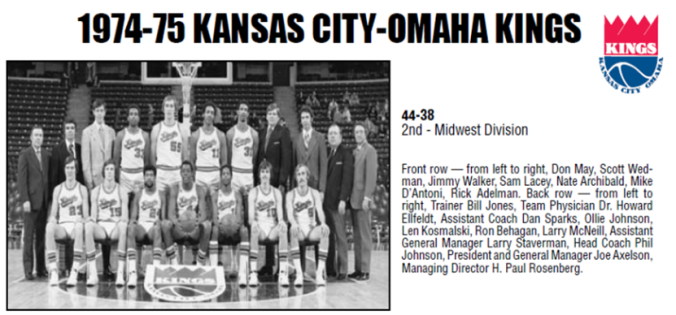

But in their last year as the Kansas City-Omaha Kings, they went 44-38 and made the playoffs, where they matched up against Bob Love, Jerry Sloan and the Chicago Bulls, whom they lost to in 6 games. However, it was the first winning record for the Kings in their history in Kansas City/Omaha area, and it set the wheels in motion for what would be more lasting on court success in Kansas City in the late 70’s and early 80’s.

The Kings had some good players during their run in Kansas City and Omaha. They had Jimmy Walker, who was a standout at Providence College and Sam Lacey, a double-double machine in the post for the Kings. Also, in 1974-1975, they had two future NBA coaches on the team in Rick Adelman, who eventually would coach the Kings to their most successful period in franchise history in Sacramento, and Mike D’Antoni, the architect of the “Seven Seconds or Less” Phoenix Suns.

However, no player was more important during the Kansas City-Omaha days than Nate “Tiny” Archibald.

Archibald was originally drafted in 1970 in the second round when the Kings were still the Royals in Cincinnati in 1970 out of the University of Texas El-Paso (which was formerly Texas Western, which was profiled in the film “Glory Road”). Archibald was a New York streetball legend who made his name on the playgrounds throughout the city, especially in the South Bronx. Unlike some high school players out of New York, Archibald’s high school accomplishments did not match his playground ones, as he only played one and a half-years of basketball at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, and nearly dropped out of high school completely due to truancy. However, despite getting cut as a sophomore from the varsity team, Archibald eventually became a team captain and All-City player, though his poor academic performance during his early high school years ended up hurting him from getting more major college offers.

Tiny was the epitome of the “streetball” city player, as he was known for his strong dribbling ability and toughness on the court despite his size, and one had to wonder how he would mesh in the middle of the country where there were more farms and corn than concrete and basketball playgrounds. He didn’t have any local ties to any of the colleges (like Kansas, Kansas State, Missouri, Iowa, Iowa State, or Nebraska), which is how many expansion franchises cater to local fanbases. However, Archibald played some of his best basketball in Kansas City, especially during the franchise’s time in Kansas City and Omaha, and Kings fans seemed to endear to him, despite his unfamiliarity to them, since day one.

In his first season as a Kansas City-Omaha King, Archibald proved he was one of the league’s superstars, which helped put the Kings, (and consequently Kansas City and Omaha) on the national media’s radar. He made the All-Star team that year and led the league in minutes played, field goals made, field goals attempted, assists and points scored (he averaged 34 points per game and 11.4 assists per game). Archibald was a one-man team of sorts and he did so from the point guard position and as one of the smaller men on the floor on a night in and night out basis. Archibald regressed a little bit the following season (not a surprise considering all the turmoil going on with the coaching situation), but in the final year as the Kansas City and Omaha Kings, Archibald was the key component to the Kings 44-38 record and appearance in the playoffs. He scored 26.5 ppg and averaged 6.8 apg, while playing all 82 games. In the playoffs, Archibald was the Kings’ best player, as he averaged 20.2 ppg during the six-game series.

While he continued his success on the court as the Kings made the move on a permanent basis to Kansas City, one could argue that Archibald saw his best years when they were split between Kansas City and Omaha. When you watch highlights of Archibald, he continues to amaze, and it’s easy to see how he influenced the game today. His ball handling skills, his jump shot, his scoring ability, his speed on the court. Archibald had a grasp of the game that not many players, let alone point guards, have had in NBA history. We hear all the time of players like Pete Maravich and Jerry West and Magic Johnson and Oscar Robertson impacting point guards of today. That being said, Archibald also deserves to be in that mix, especially when you consider his size, his impact on professional basketball in the Midwest, and his ability to overcome a lot of odds and roadblocks in his personal life to be successful. Tiny is in the Hall of Fame for a reason and the video below should be further reason why.

It’s fun to watch him play back then. The way he creates with the ball, the way he cuts through defenders on the way to the basket, the way he scores with such versatility and ease, and how he displays such bravado on the court and humility off of it. It reminds the younger generations that there were entertaining one-man shows in the NBA prior to Jason Williams and Stephen Curry.

It’s too bad there are not more tapes and highlights of Archibald in the NBA vault.

Professional basketball most likely will not be coming back to Kansas City anytime soon, if ever. And the same could be said for Omaha as well, which doesn’t have any professional sports franchise other than a minor league baseball team. And yet for three seasons, NBA basketball was played in the Midwest between two cities and among four states. For three seasons, the Kings were not just a city’s NBA team, but an overlooked geographical area’s, and they produced some memorable teams and some memorable players. Yes, there were no championships in Kansas City-Omaha, nor were there any championships when the franchise was solely in Kansas City. And that is too bad, especially since championships can save franchises financially and spiritually (fans won’t want to part with a team that won a championship for their community).

But, Kansas City and Omaha Kings fans were a witness to professional basketball. They were a witness to the playoffs, where the Kings won two home games in front of the raucous Kemper Arena faithful (they used alternate home and away games every game rather than every two like today). And they were witness to a Hall of Famer playing the best and most entertaining basketball of his career in the Heart of America, the Midwest, typically seen as the “Flyover States.”

For three years, Kansas City and Omaha had something truly wonderful, not to mention something people currently in Kansas City and Omaha will never see in those cities again.

I know Kings fans say they envy those Kings fans who were around when the Kings were in Kansas City. I know I can say I envy those Kings fans who will be there for the new arena opening this October in Sacramento (though I know I will see a Kings game at some point in the new arena, so my envy is not that high).

But I think those currently in Kansas City and Omaha, especially those who grow up here in the post-Kings era, can definitely say they envy those who were Kings fans from 1972-1975. Because they missed out on so much, and will never get that opportunity down the road in Kansas City and Omaha. Those three years were a simply a comet of basketball wonder in the Midwest.

And I envy that, even as a Kansas City transplant.